The Berlin Wall, which stood as a physical and ideological symbol of the Cold War for nearly 30 years, was torn down in 1989, marking the beginning of the end of the division of East and West Germany, and the collapse of the Soviet Union’s influence over Eastern Europe. The fall of the Berlin Wall was one of the most significant events in modern history, symbolizing the end of communist rule in Eastern Europe and the reunification of Germany. This article explores the background, socio-cultural, economic, and political reasons behind the fall of the Berlin Wall, the key events that led to its collapse, and its profound impact on global politics.

After World War II, Germany was divided into four occupation zones controlled by the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union. Berlin, located deep within the Soviet-controlled zone, was also divided into four sectors. Over time, political tensions between the Soviet Union and the Western Allies led to the formation of two German states: the capitalist West Germany (Federal Republic of Germany) and the communist East Germany (German Democratic Republic). The city of Berlin became the epicenter of this division, with West Berlin being a democratic enclave surrounded by communist East Germany.

The Berlin Wall was erected on August 13, 1961, by the East German government under the direction of the Soviet Union. The Wall was built to stop the massive migration of East Germans to the West, which had been occurring in large numbers since the 1940s. Between 1949 and 1961, around 2.7 million East Germans had escaped to West Germany, often through Berlin, leading to a "brain drain" that destabilized the communist government in East Germany. The Wall physically and ideologically divided East and West Berlin, restricting movement between the two sectors and becoming a powerful symbol of the Cold War.

The oppressive nature of the East German regime, backed by Soviet control, contributed to widespread dissatisfaction among the people. In East Germany, citizens faced restrictions on freedom of speech, political dissent, and the ability to travel freely. The government maintained control through the Stasi (secret police) and other surveillance mechanisms. Despite the government's strict control, many East Germans longed for greater political freedoms, access to Western culture, and economic opportunities available in the capitalist West.

East Germany, like other Eastern Bloc countries, faced significant economic challenges under a centrally planned communist system. The economy struggled with inefficiencies, stagnation, and shortages of goods. While West Germany, aligned with the capitalist model, experienced rapid economic growth, East Germany remained impoverished, with its citizens facing lower living standards and fewer consumer goods. Many East Germans were dissatisfied with the contrast between their country’s economic hardships and the prosperity in West Germany, which only fueled the desire for change.

The political landscape in the Eastern Bloc began to change in the mid-1980s with the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev as the leader of the Soviet Union. Gorbachev introduced a series of reforms known as glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) to address the economic stagnation and political repression that plagued the Soviet Union and its satellite states. These reforms encouraged more political freedom, the openness of government practices, and greater autonomy for Eastern European countries. In Eastern Europe, these reforms sparked demands for change and greater political freedom.

By the late 1980s, the Soviet Union was weakening. Gorbachev's efforts to reform the Soviet economy and political system, combined with the increasing influence of reformist movements in Eastern Europe, led to a loosening of Soviet control over the Eastern Bloc. The Soviet Union’s declining power made it difficult for the USSR to maintain its grip over Eastern Europe, which encouraged citizens in countries like Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany to push for political and economic change.

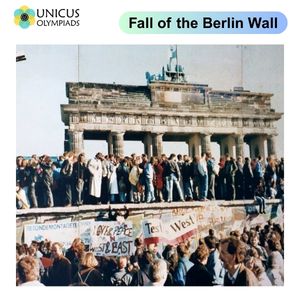

The immediate trigger for the fall of the Berlin Wall came in November 1989. In a press conference, an East German spokesperson, Günter Schabowski, mistakenly announced that East Germans could travel freely to West Berlin and other countries. This announcement, which was not well-prepared, led thousands of East Berliners to flock to the Wall, demanding to cross into the West. Border guards, who had not been informed of the policy change, were overwhelmed and opened the gates, allowing people to cross freely into West Berlin. The Wall was torn down by jubilant crowds, marking the symbolic end of the division of Berlin and the collapse of the Iron Curtain.

The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, was a watershed moment in world history. It marked the end of a divided Europe and the collapse of Soviet influence in Eastern Europe. The event was the culmination of political, economic, and cultural changes that had been building for decades, fueled by a desire for freedom, political reforms, and economic modernization. The reunification of Germany and the eventual dissolution of the Soviet Union reshaped the political landscape of Europe and led to the spread of democracy and capitalism across the former Eastern Bloc. Today, the Berlin Wall stands as a symbol of the power of peaceful revolution and the triumph of human spirit over division and oppression.